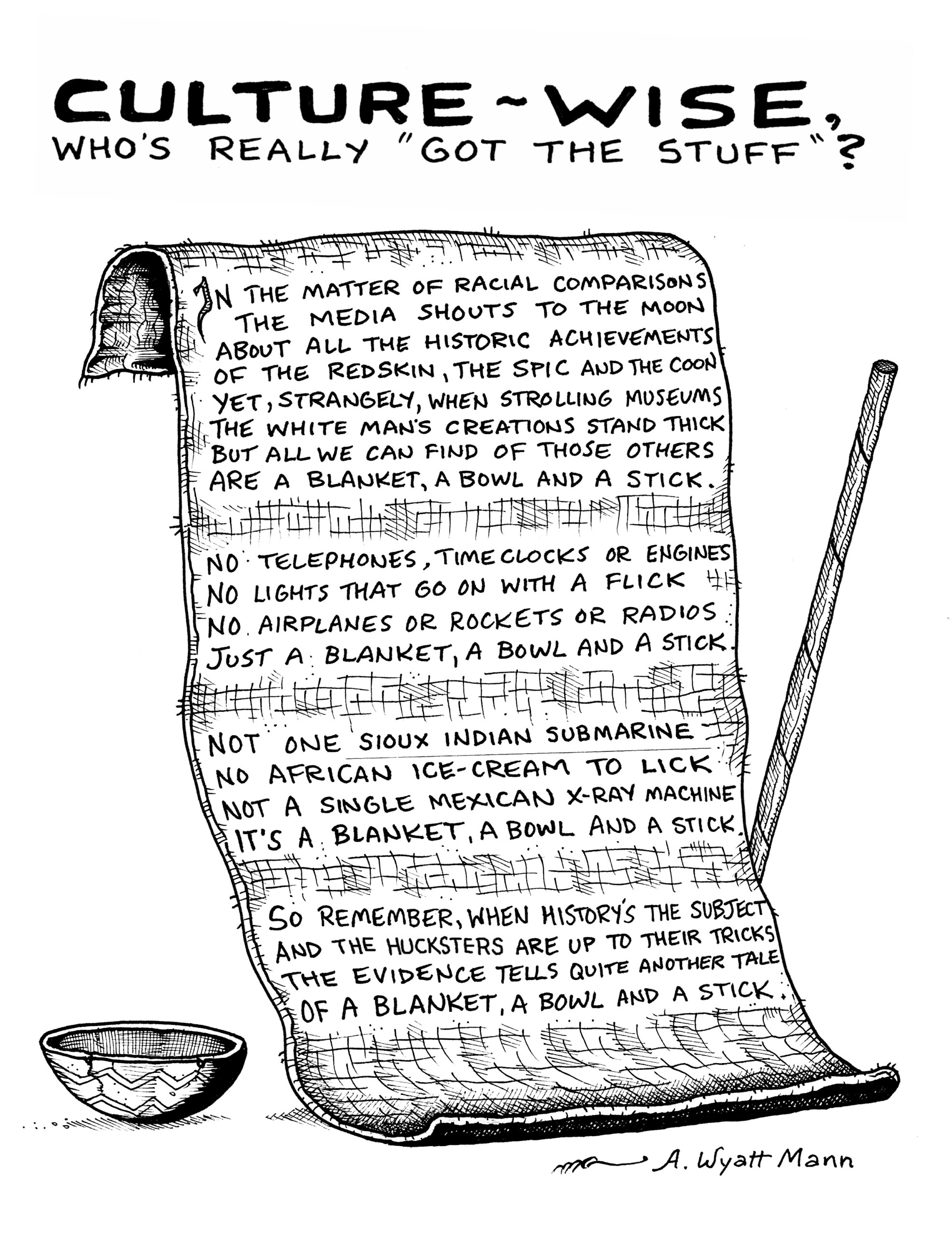

Admirers of the long-time cartoonist who uses the pseudonym A. Wyatt Mann have described him as a shadowy living legend, a guerrilla illustrator, a prophet and the inventor of the modern meme. Mann blushes at these flowery appraisals on his body of work and insists that he’s “simply a political cartoonist dedicated to bringing some balance back to a media world that leans heavily to the left”.

What is undeniable is that he has gifted the Internet with some of its most irreverent and widely shared images, including the iconic “Happy Merchant”, the prescient “Watcha doin’ Rabbi?” and the astute “Around Blacks, Never Relax”. Even the pervasive expression of hip gibberish, “Bix Nood”, was plucked from one of his captions. His unique arsenal of “Manntoons” become widely recognized as an integral part of online counter-culture. Very kindly, Mann recently agreed to be interviewed by phone about his life and work.

Hi Wyatt – Thank you for taking the time to talk to us.

My Pleasure.

I’ve noticed that many leftists often call your work crude, disgusting and overtly racist, but they rarely pause to comment on whether or not they are remotely honest or accurate.

Yes, that’s pretty much a standard tactic of those gutless goofballs. They won’t tackle any subject that might lead to a debate. Apparently, when your whole universe revolves around incessant whining and perpetual agenda-driven outrage, you become incapable of judging anything on its true merit. I mean, can you think of anything more out of step with nature and reality than your typical American Marxist?

I’ve come to view these dolts as a sad, unrealized lot who seek to dodge sunny logic and retreat to a la-la-landscape fogged by delusion and deceit. I take utter delight depicting them as the loathsome simpletons and miscreants that they are by calling their baffling political beliefs into question.

What would you say inspired you to take up political cartooning?

I’d say it was more like political cartooning took me up. At an early age, when I’d thumb through magazines and come to a political cartoon, I became fascinated by the hefty punch that satirical artwork possessed and how a mocking portrait of a powerful figure could be used to deflate them. President Nixon was routinely savaged in this way . . . so much so, that it became difficult to conjure an image of him in your mind without the shifty eyes and quivering jowls that cartoonists always added. I began experimenting with exaggerating facial features and expressions and found I had a real knack for it.

Can you tell us something about your early days experimenting with art?

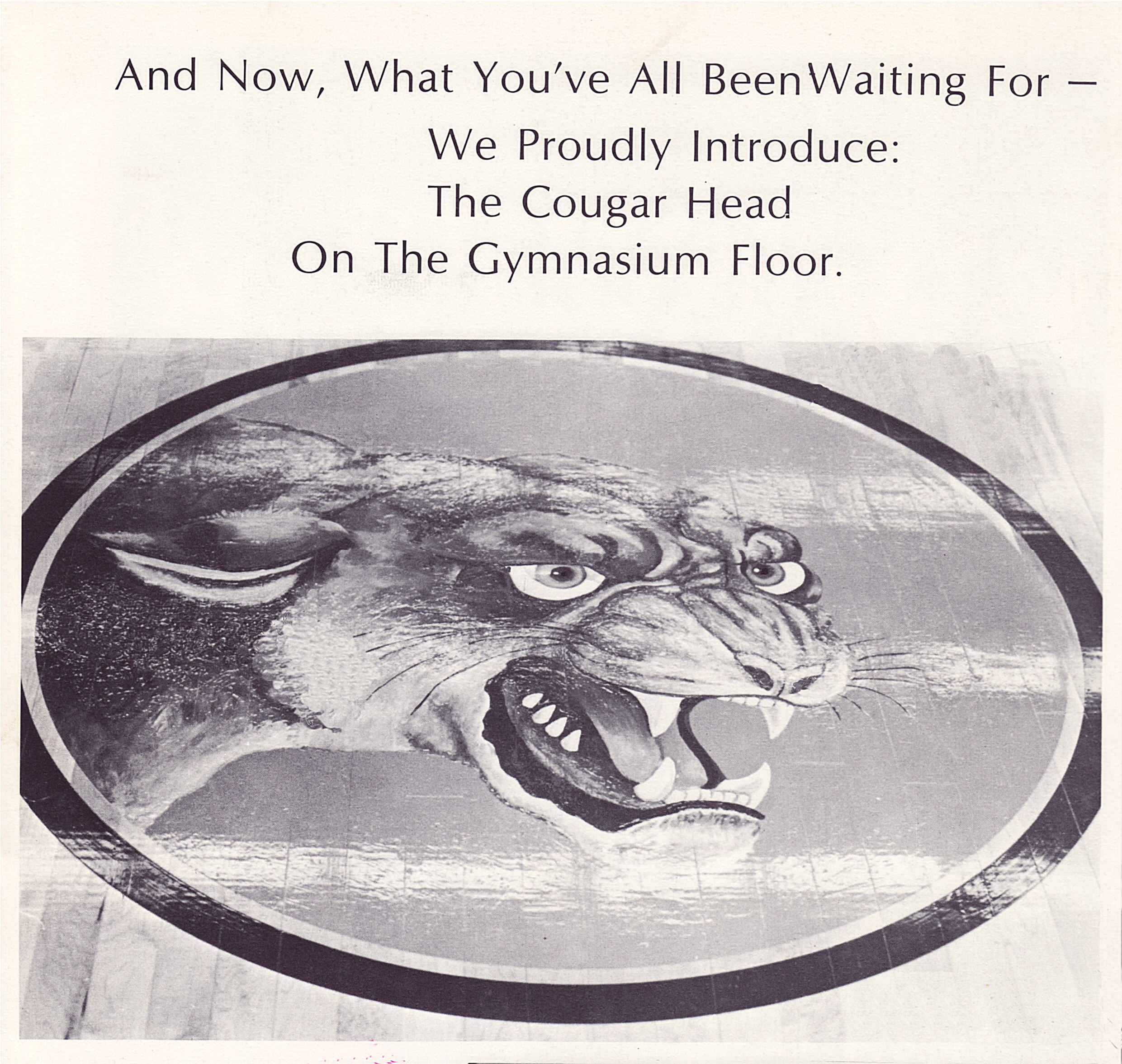

According to family lore, it appears I was always able to draw well . . . once grown, my mother informed me that my first “masterpiece” was rendered in ballpoint pen when I was but two years old. It was a large depiction of a choo-choo train that ran the whole length of a hallway in our home. She told me that the eerie thing about it was that it didn’t look at all like the scrawling of a child, but had very defined detail and symmetry which left her astonished . . . she said she was so impressed that she couldn’t bring herself to punish me for the act of vandalism that left her scrubbing the wall furiously for days. During my early teens, I found myself always being pressed into service, making huge signs for charity bake sales, neighborhood barbecues and any type of school function you can name . . . I actually came to dislike being “artistic” and for many years considered artwork nothing more than a bothersome chore. At age fifteen, my principal drafted me to paint the school emblem, a cougar, on the gym floor (this was in Georgia).